Louis Budenz was an anticommunist informer who gave the FBI hundreds of names of people he claimed were communists. According to Robert M. Lichtman, Budenz was a prolific informer, but it had not always been that way. He was once a devoted communist, and worked as editor for its flagship publication the Daily Worker.

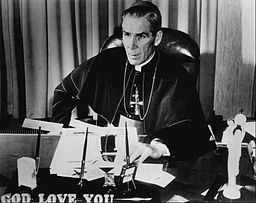

Budenz made a dramatic exit from the Party in 1945, when he knelt before the anticommunist Monsignor Fulton Sheen and devoted himself to the Catholic Church. The Party did not know he left until reading about it in the newspaper. As editor of the Daily Worker, Budenz had frequently attacked Sheen, who had a popular radio program where he denounced communism. This made Budenz’s exit more dramatic.

In 1946, Budenz testified before the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) where he mentioned that he was ordered not to write about Juliet Stuart Poyntz in the Daily Worker. Budenz’s testimony was buried in newspapers and did not make headlines. But the following year he published a memoir titled This is my story. In it he described Poyntz’s disappearance and the Party’s silence on the issue. He also claimed that it was widely accepted that she had been murdered, though he only had rumor as evidence.

In the wake of Carlo Tresca’s murder, his friends had created a Memorial Committee to push the police to solve the murder. After Budenz’s book was published, the Committee under socialist Norman Thomas’s leadership, urged the New York Assistant District Attorney to put Budenz on the stand to find out if he knew more about Tresca and Poyntz. Unfortunately for the committee he did not provide any new information.

Budenz’s career as an anticommunist was quite lucrative. In 1953 he made $70,000 from it. But his accusations were often not substantiated and even the FBI doubted some of his information. Budenz like many other anticommunists had to try and remain relevant by elaborating on stories and sometimes fabricating them. As Lichtman claims, some of the people Budenz named as communists had no idea that he had done so. The Daily Worker, his former employer, challenged much of what he said. Budenz, like many of his anticommunist comrades, used Poyntz’s disappearance to dramatize the so-called communist threat, though they could never prove what happened, but evidence was never really that important to anticommunists.